New Zealand Plans for Rearmament

New Zealand releases new Defence Capability Plan

On April 7th, the New Zealand Ministry of Defence released its Defence Capability Plan, which outlined the country’s spending priorities over the next several years. Wellington aims to nearly double defense spending over the next eight years from a little over 1 percent to 2 percent of GDP.

Since the end of the Cold War, New Zealand has largely prioritized territorial defense over expeditionary capabilities or collective defense commitments. This posture—characterized by modest defense spending and limited global engagement—has drawn criticism as a form of strategic apathy. Critics argue that Wellington has effectively freeridden on the security umbrella provided by stronger partners like the United States, Australia, and Japan.

The consequences of this approach are visible. Regular Force personnel declined from 12,400 in 1985 to just 8,946 in 2024. New Zealand retired its air combat wing in 2001, leaving a significant capability gap. Most recently, in October 2023, one of New Zealand’s nine naval vessels ran aground and sank near Samoa—an incident that raised concerns about both training and readiness. Additionally, defense spending as a share of GDP has also fallen sharply since 1980, reinforcing perceptions that New Zealand’s defense posture has not kept pace with evolving regional threats.

New Zealand’s newly announced Defence Capability Plan, if implemented, aims to reverse years of underinvestment in its military. This plan reflects a broader strategic realignment in Wellington. Like many countries, New Zealand long attempted to balance deep trade ties with China and a security partnership with the United States. But growing security concerns—and a rising perception that economic dependence on China is a vulnerability—have prompted a significant strategic shift.

A recent shock to New Zealand’s regional influence underscored these concerns. Despite New Zealand’s constitutional responsibility for the foreign and defense policy of the Cook Islands, the territory unexpectedly entered into a strategic partnership with Beijing. The move blindsided Wellington and revealed how Chinese influence can undermine New Zealand’s role in the Pacific. The episode has deepened concerns about Beijing’s encroachment and accelerated New Zealand’s pivot toward greater defense preparedness. The US-China competition underscores New Zealand’s recent shift.

New Zealand Government: Defence Capability Plan:

The Indo-Pacific is a primary geographical theatre for strategic competition, most visibly between China and the United States. China’s assertive pursuit of its strategic objectives is the principal driver for strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific, and it continues to use all of its tools of statecraft in ways that can challenge both international norms of behaviour and the security of other states. Of particular concern is the rapid and non-transparent growth of China’s military capability.

As New Zealand looks to dramatically increase defense spending, it has identified three key areas of investment to deliver a Defense Force that is:

Combat capable with enhanced lethality and deterrent effect

A force multiplier with Australia and interoperable with partners

Innovative and has improved situational awareness

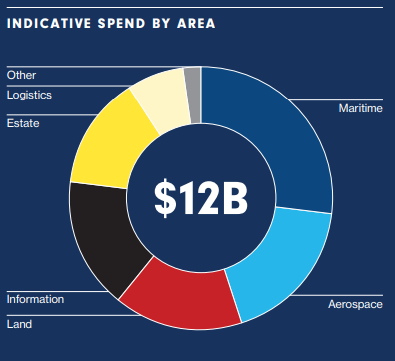

The $12 billion over the next four years will be broken down by these areas:

Below are some of the investments that NZDF outlines from 2025 to 2028:

$100-300M for enhanced strike capabilities

$300-600M for frigate sustainment program

$50-100M for uncrewed autonomous vessels

Up to $50M for javelin anti-tank missile upgrade

$300-600M for upgraded Army network capability

Up to $50M for counter uncrewed aerial systems (UAS)

$100-300M for long-range remotely piloted aircraft

$100-300M for enhancing cyber security capabilities

$1B plus for modern military enterprise resource management software

Up tom $50M for defense science and technology

$100-300M for technology accelerator

$100-300M for digital modernization

$100-300M for information management

A cornerstone of New Zealand’s implementation strategy is deepening defense ties with Australia. Notably, the United States is only briefly mentioned in the Defence Capability Plan—and only in the context of broader Indo-Pacific security dynamics. Instead, New Zealand places primary emphasis on advancing joint procurement, interoperability, and strategic alignment with Canberra.

This approach carries indirect but meaningful benefits for Washington. Australia is a key and increasingly capable ally of the United States. Enhanced cooperation between Australia and New Zealand on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), maritime domain awareness, and defense industrial collaboration not only strengthens regional security but also supports U.S. strategic objectives. While direct U.S.–New Zealand engagement will continue, a more integrated and capable ANZAC defense partnership ultimately serves American interests in the Indo-Pacific.

Alliance Insights: Key Articles This Week

Japan:

Nikkei Asia: Japan and NATO to ramp up defense industry cooperation

Nikkei Asia: Japan-U.S. missile defense project is 'model for cooperation': Northrop CEO

South Korea:

Yonhap News Agency: S. Korea, U.S. hold joint air exercise involving B-1B bomber

Yonhap News Agency: S. Korea, U.S. inked new joint wartime contingency plan last year amid advancing N.K. threats: USFK commander

Philippines:

Naval News: Philippine Coast Guard, OCEA sign vessel maintenance contract

Breaking Defense: Philippines cleared to buy F-16s at estimated $5.6B

India:

Breaking Defense: India puts Metrea on contract for commercial air refueling, invests in helicopters

Breaking Defense: India to double Hanwha self-propelled howitzer buy, will manufacture locally

Nikkei Asia: India's Modi agrees to step up defense cooperation with Sri Lanka

Financial Times: India launches biggest-ever joint naval exercises in Africa

New Zealand:

Great Power Competition: